|

|

| Reception | Room 1 | Room 2 | Room 3 | Room 4 | Final Round | Slide Show |

Play-by-Play | Photos | Problem Analysis

Problem Set Analysis & Opinion

by lbackstrom,

TopCoder Member

Thursday, December 4, 2003

AvoidRoads

Used as: Division 1 - Level 1:

This is a classic dynamic programming problem. We can solve it iteratively, caching the results as we go, or we can use memoization. First, we'll go over the iterative solution. In both methods, we need to observe that ignoring blocked roads, the number of ways to get to position (x,y), ways(x,y), is ways(x-1,y)+ways(x,y-1). We have to modify this slightly to account for the blocked roads, but doing so is pretty simple, just don't add along a blocked road. So, we can write a naive recursive solution as:

long ways(int x, int y){

if(x==0&&y==0)return 1;

long ret = 0;

if(!blocked(x-1,y,x,y))ret+=ways(x-1,y);

if(!blocked(x,y-1,x,y))ret+=ways(x,y-1);

return ret;

}

However, this solution will time out drastically. But, a simple fix will make it run in time. We cache the answers so that we only calculate a value once, a technique called memoization:

long ways(int x, int y){

if(x==0&&y==0)return 1;

if(cached(x,y))return cache[x][y];

long ret = 0;

if(!blocked(x-1,y,x,y))ret+=ways(x-1,y);

if(!blocked(x,y-1,x,y))ret+=ways(x,y-1);

cache[x][y] = ret;

return ret;

}

That is the memoized solution; the iterative solution is similar, but doesn't use recursion. Instead, we just loop over all x,y coordinates, and put values in our array:

ways[0][0] = 1;

for(int x = 0; x<=width; x++)

for(int y = 0; y<=height; y++){

if(!blocked(x-1,y,x,y))ways[x][y]+=ways[x-1][y];

if(!blocked(x,y-1,x,y))ways[x][y]+=ways[x][y-1];

}

return ways[width][height];

PipePath

Used as: Division 1 - Level 2:

While this problem appears to require some more advanced algorithm, it turns out that we can solve it using little more than a shortest path algorithm. The key to this observation, is that there aren't that many possibilities for the capacity of a path. Since the capacity of a path is the minimum capacity of the edges along it, the number of possible capacities we can obtain along a path from source to sink is at most the number of edges. So, to find the best ratio, we can simply consider the lowest cost path which only uses edges whose capacity is greater than or equal to a cutoff. The values to use for the cutoff are exactly identical to the capacities of all the edges. So, in pseudocode, this goes as:

double ratio = 0;

foreach(unique capacity cap){

find the shortest path from source to sink,

each of whose edges has a capacity of at least cap

if(there is some path){

ratio = max(ratio, cap/pathLength)

}

}

return ratio;

Since there are at most about 50*12 edges, and Floyd-Warshall runs in O(n^3), even a slow implementation should run fast enough. There are solutions that are significantly faster, but nothing really clever was required with only 50 nodes. The one caveat to watch out for is that multiple edges are allowed. But, its pretty easy to deal with this by always using the the lowest cost edge whose capacity is sufficiently high.

RookAttack

Used as: Division 1 - Level 3:

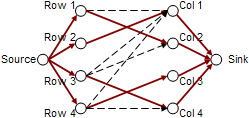

Speaking of sources and sinks, this problem is best solved using a max flow algorithm, though the reduction is a little tricky. As in all max flow reductions, we'll start by adding a source node and a sink node. Since we can have at most one rook per row, we add a node corresponding to each row, and an edge from the source to each of these nodes, with capacity 1. We also add a node corresponding to each column, and an edge from these nodes to the sink of capacity 1.

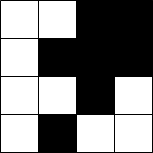

Now, the question is how to connect the rows and columns. For each unblocked location in the board, we add an edge from the row node to the column node for that location. This has the effect of allowing us to place a rook at that location, which fills up the capacity for the corresponding row and column. As an example, consider the board to the left.

From this board, we can construct the network to the right, where each edge has capacity 1. Each edge from the row nodes to the column nodes represents an empty space in the board. So, since row 1, column 1 is empty, there is an edge from from the row 1 node to the column 1 node. If we run a max flow algorithm on this graph, we find the flow defined by the bold, red edges in the image. Since the flow is 4, we can fit 4 rooks on the board. To see where the rooks go, we just have to look at which edges are used. The edge from row 2 to column 1 is used, so there is a rook at (2,1). Similarly, there are rooks at (1,2), (3,4) and (4,3).

So, once we construct the graph, the return value is just the max flow. The graph is pretty big, with as many as 600 nodes, and 90,000 edges. But, since we have at most 300 rows, the flow is at most 300, and even Ford-Fulkerson runs in time (300*O(|edges|)).