By medv– Topcoder Member

Discuss this article in the forums

In addition to being a Topcoder member, medv is a lecturer in Kiev National University’s cybernetics faculty.

Prime numbers and their properties were extensively studied by the ancient Greek mathematicians. Thousands of years later, we commonly use the different properties of integers that they discovered to solve problems. In this article we’ll review some definitions, well-known theorems, and number properties, and look at some problems associated with them.

A prime number is a positive integer, which is divisible on 1 and itself. The other integers, greater than 1, are composite. Coprime integers are a set of integers that have no common divisor other than 1 or -1.

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic:

Any positive integer can be divided in primes in essentially only one way. The phrase ‘essentially one way’ means that we do not consider the order of the factors important.

One is neither a prime nor composite number. One is not composite because it doesn’t have two distinct divisors. If one is prime, then number 6, for example, has two different representations as a product of prime numbers: 6 = 2 * 3 and 6 = 1 * 2 * 3. This would contradict the fundamental theorem of arithmetic.

Euclid’s theorem:

There is no largest prime number.

To prove this, let’s consider only n prime numbers: p1, p2, …, pn. But no prime pi divides the number

N = p1 * p2 * … * pn + 1,

so N cannot be composite. This contradicts the fact that the set of primes is finite.

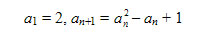

Exercise 1. Sequence an is defined recursively:

Prove that ai and aj, i ¹ j are relatively prime.

Hint: Prove that an+1 = a1a2…an + 1 and use Euclid’s theorem.

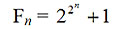

Exercise 2. Ferma numbers Fn (n ≥ 0) are positive integers of the form

Prove that Fi and Fj, i ≠ j are relatively prime.

Hint: Prove that Fn +1 = F0F1F2…Fn + 2 and use Euclid’s theorem.

Dirichlet’s theorem about arithmetic progressions:

For any two positive coprime integers a and b there are infinitely many primes of the form a + n*b, where n > 0.

Trial division:

Trial division is the simplest of all factorization techniques. It represents a brute-force method, in which we are trying to divide n by every number i not greater than the square root of n. (Why don’t we need to test values larger than the square root of n?) The procedure factor prints the factorization of number n. The factors will be printed in a line, separated with one space. The number n can contain no more than one factor, greater than n.

void factor(int n) {

int i;

for(i=2;i<=(int)sqrt(n);i++) {

while(n % i == 0) {

printf("%d “,i);

n /= i;

}

}

if (n > 1) printf(”%d",n);

printf("\n");

}

Consider a problem that asks you to find the factorization of integer g(-231 < g <231) in the form

g = f1 x f2 x … x fn or g = -1 x f1 x f2 x … x fn

where fi is a prime greater than 1 and fi ≤ fj for i < j.

For example, for g = -192 the answer is -192 = -1 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 3.

To solve the problem, it is enough to use trial division as shown in function factor.

Sieve of Eratosthenes:

The most efficient way to find all small primes was proposed by the Greek mathematician Eratosthenes. His idea was to make a list of positive integers not greater than n and sequentially strike out the multiples of primes less than or equal to the square root of n. After this procedure only primes are left in the list.

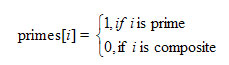

The procedure of finding prime numbers gen_primes will use an array primes[MAX] as a list of integers. The elements of this array will be filled so that

At the beginning we mark all numbers as prime. Then for each prime number i (i ≥ 2), not greater than √MAX, we mark all numbers ii, i(i + 1), … as composite.

void gen_primes() {

int i,j;

for(i=0;i<MAX;i++) primes[i] = 1;

for(i=2;i<=(int)sqrt(MAX);i++)

if (primes[i])

for(j=i;ji<MAX;j++) primes[ij] = 0;

}

For example, if MAX = 16, then after calling gen_primes, the array ‘primes’ will contain next values:

| i | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| primes[i] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Goldbach’s Conjecture:

For any integer n (n ≥ 4) there exist two prime numbers p1 and p2 such that p1 + p2 = n. In a problem we might need to find the number of essentially different pairs (p1, p2), satisfying the condition in the conjecture for a given even number n (4 ≤ n ≤ 2 15). (The word ‘essentially’ means that for each pair (p1, p2) we have p1 ≤p2.)

For example, for n = 10 we have two such pairs: 10 = 5 + 5 and 10 = 3 + 7.

To solve this,as n ≤ 215 = 32768, we’ll fill an array primes[32768] using function gen_primes. We are interested in primes, not greater than 32768.

The function FindSol(n) finds the number of different pairs (p1, p2), for which n = p1 + p2. As p1 ≤ p2, we have p1 ≤ n/2. So to solve the problem we need to find the number of pairs (i, n – i), such that i and n – i are prime numbers and 2 ≤ i ≤ n/2.

int FindSol(int n) {

int i,res=0;

for(i=2;i<=n/2;i++)

if (primes[i] && primes[n-i]) res++;

return res;

}

Euler’s totient function

The number of positive integers, not greater than n, and relatively prime with n, equals to Euler’s totient function φ (n). In symbols we can state that

φ (n) ={a Î N: 1 ≤ a ≤ n, gcd(a, n) = 1}

This function has the following properties:

If p is prime, then φ § = p – 1 and φ (pa) = p a * (1 – 1/p) for any a.

If m and n are coprime, then φ (m * n) = φ (m) * φ (n).

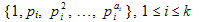

If n = , then Euler function can be found using formula:

φ (n) = n * (1 – 1/p 1) * (1 – 1/p 2) * … * (1 – 1/p k)

The function fi(n) finds the value of φ(n):

int fi(int n) {

int result = n;

for(int i=2;i*i <= n;i++) {

if (n % i == 0) result -= result / i;

while (n % i == 0) n /= i;

}

if (n > 1) result -= result / n;

return result;

}

For example, to find φ(616) we need to factorize the argument: 616 = 23 * 7 * 11. Then, using the formula, we’ll get:

φ(616) = 616 * (1 – 1/2) * (1 – 1/7) * (1 – 1/11) = 616 * 1/2 * 6/7 * 10/11 = 240.

Say you’ve got a problem that, for a given integer n (0 < n ≤ 109), asks you to find the number of positive integers less than n and relatively prime to n. For example, for n = 12 we have 4 such numbers: 1, 5, 7 and 11.

The solution: The number of positive integers less than n and relatively prime to n equals to φ(n). In this problem, then, we need do nothing more than to evaluate Euler’s totient function.

Or consider a scenario where you are asked to calculate a function Answer(x, y), with x and y both integers in the range [1, n], 1 ≤ n ≤ 50000. If you know Answer(x, y), then you can easily derive Answer(kx, ky) for any integer k. In this situation you want to know how many values of Answer(x, y) you need to precalculate. The function Answer is not symmetric.

For example, if n = 4, you need to precalculate 11 values: Answer(1, 1), Answer(1, 2), Answer(2, 1), Answer(1, 3), Answer(2, 3), Answer(3, 2), Answer(3, 1), Answer(1, 4), Answer(3, 4), Answer(4, 3) and Answer(4, 1).

The solution here is to let res(i) be the minimum number of Answer(x, y) to precalculate, where x, y Î{1, …, i}. It is obvious that res(1) = 1, because if n = 1, it is enough to know Answer(1, 1). Let we know res(i). So for n = i + 1 we need to find Answer(1, i + 1), Answer(2, i + 1), … , Answer(i + 1, i + 1), Answer(i + 1, 1), Answer(i + 1, 2), … , Answer(i + 1, i).

The values Answer(j, i + 1) and Answer(i + 1, j), j Î{1, …, i + 1}, can be found from known values if GCD(j, i + 1) > 1, i.e. if the numbers j and i + 1 are not common primes. So we must know all the values Answer(j, i + 1) and Answer(i + 1, j) for which j and i + 1 are coprime. The number of such values equals to 2 * φ (i + 1), where φ is an Euler’s totient function. So we have a recursion to solve a problem:

res(1) = 1,

res(i + 1) = res(i) + 2 * j (i + 1), i > 1

Euler’s totient theorem:

If n is a positive integer and a is coprime to n, then a φ (n) º 1 (mod n).

Fermat’s little theorem:

If p is a prime number, then for any integer a that is coprime to n, we have

a p ≡ a (mod p)

This theorem can also be stated as: If p is a prime number and a is coprime to p, then

a p -1 ≡ 1 (mod p)

Fermat’s little theorem is a special case of Euler’s totient theorem when n is prime.

The number of divisors:

If n =  , then the number of its positive divisors equals to

, then the number of its positive divisors equals to

(a1 + 1) * (a2 + 1) * … * (ak + 1)

For a proof, let A i be the set of divisors  . Any divisor of number n can be represented as a product x1 * x2 * … * x k , where xi Î Ai. As |Ai| = ai + 1, we have

. Any divisor of number n can be represented as a product x1 * x2 * … * x k , where xi Î Ai. As |Ai| = ai + 1, we have

(a1 + 1) * (a2 + 1) * … * (ak + 1)

possibilities to get different products x1 * x2 * … * xk.

For example, to find the number of divisors for 36, we need to factorize it first: 36 = 2² * 3². Using the formula above, we’ll get the divisors amount for 36. It equals to (2 + 1) * (2 + 1) = 3 * 3 = 9. There are 9 divisors for 36: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 36.

Here’s another problem to think about: For a given positive integer n (0 < n < 231) we need to find the number of such m that 1 ≤ m ≤ n, GCD(m, n) ≠ 1 and GCD(m, n) ≠ m. For example, for n = 6 we have only one such number m = 4.

The solution is to subtract from n the amount of numbers, coprime with it (its amount equals to φ(n)) and the amount of its divisors. But the number 1 simultaneously is coprime with n and is a divisor of n. So to obtain the difference we must add 1. If n =  is a factorization of n, the number n has (a1 + 1) * (a2 + 1) * … * (ak + 1) divisors. So the answer to the problem for a given n equals to

is a factorization of n, the number n has (a1 + 1) * (a2 + 1) * … * (ak + 1) divisors. So the answer to the problem for a given n equals to

n – φ(n) – (a1 + 1) * (a2 + 1) * … * (ak + 1) + 1

Practice Room:

Want to put some of these theories into practice? Try out these problems, from the Topcoder Archive:

Refactoring (SRM 216)

PrimeAnagrams (SRM 223)

DivisibilityCriteria (SRM 239)

PrimePolynom (SRM 259)

DivisorInc (SRM 302)

PrimePalindromic (SRM 303)

RugSizes (SRM 304)

PowerCollector (SRM 305)

PreprimeNumbers (SRM 307)

EngineersPrimes (SRM 181)

SquareFree (SRM 190)